The Radioactive Waste in Our Backyard

What’s Already Here; and, What’s on the Way — a Two-Part Shore Report Series

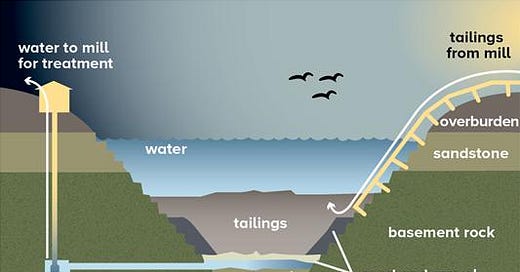

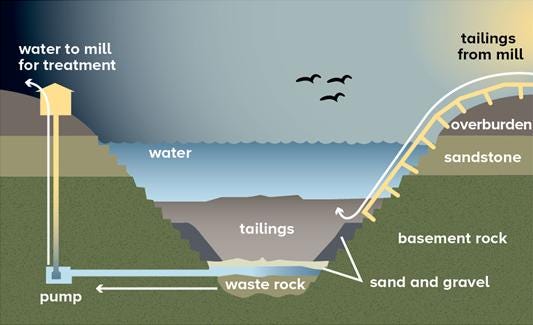

Illustration of a uranium tailings storage facility, courtesy Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission.

What’s Already Here

Annual report on management of Elliot Lake waste sites delivered to Council

Against the backdrop of ongoing concern for a waste rock and tailings project at Agnew Lake, the North Shore City of Elliot Lake has recently received a positive report on its own long-term legacy of radioactive mine waste.

At its March 24th meeting, Elliot Lake City Council received an annual update from BHP, a global mining company headquartered in Australia, and the entity tasked with cleaning and maintaining most of Elliot Lake’s uranium tailings and waste sites, the result of the city’s history as the “Uranium Capital of the World.”

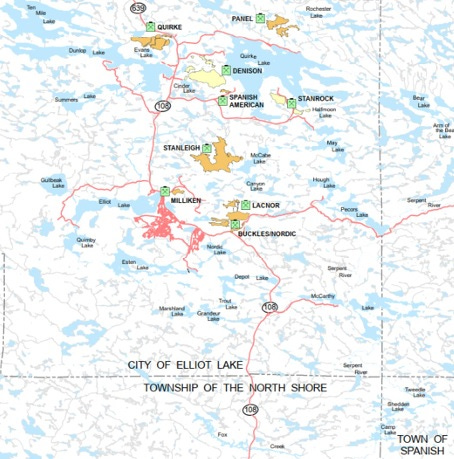

Map of legacy mine sites in and around Elliot Lake, courtesy BHP report.

Twelve uranium mine sites in one form or another operated around Elliot Lake between the 1950s and 90s, though that number was quickly consolidated into two companies, Rio Algom and Denison. While local extraction ceased and mine sites closed permanently by the 1990s, the serious long-term task of managing radioactive mine tailings and mineralized waste rock was just beginning. In a corporate merger early in this century, BHP took over the former Rio Algom sites.

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), a Government of Canada agency, also monitors the sites. A 2019 Independent Environmental Monitoring Program (IEMP) found “that the public and the environment around the Elliot Lake historical mine sites are protected and that there are no expected health or environmental impacts.”

CNSC lists 14 decommissioned uranium mines in Ontario, with the Elliot Lake BHP sites, two Denison Mines sites in Elliot Lake as well, and the Agnew Lake tailings management area within the region of Lake Huron’s North Shore. The rest are near Bancroft to the east.

BHP local site superintendent Maxime Morin presents to Elliot Lake Council. Image courtesy Elliot Lake City Council.

The BHP team — local Site Superintendent Maxime Morin in the Council chamber, and several others online from various BHP offices worldwide — delivered a consistently positive report to Elliot Lake Council, highlighting regularly planned maintenance and upgrading and the building and maintaining of trail and recreational systems for the use of locals. Elliot Lake’s elected leaders accepted the report without comment or question. Mayor Andrew Wannan thanked BHP for the community engagement work they do in Elliot Lake, including the provision of an emergency generator on short notice when a power outage disrupted the city’s 2024 Street Dance.

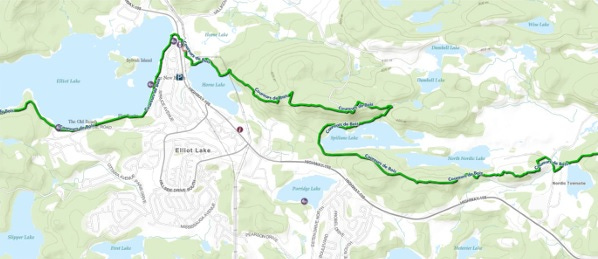

The TransCanada Trail winds through Elliot Lake, past a number of tailings sites. Image courtesy BHP.

BHP Limited was formed in 2000 after a merger between extraction firms Broken Hill Proprietary and Billiton. It is considered the largest mining operation in the world, and does considerable business in Canada (with main offices in Saskatoon), including the massive Jansen Potash Project in Saskatchewan, copper exploration, and closed site remediation. The Elliot Lake operation is part of what the company calls Legacy Asset management.

BHP was not part of the original uranium extraction operations on the North Shore, but took over responsibility for much of the cleanup and tailings maintenance as part of their expanded Canadian business. According to their report, 25 historic mining sites throughout North America were acquired by BHP in mergers and acquisitions “close to or after their closure.” BHP then assumed responsibility for the rehabilitation and restoration of those sites, including in Elliot Lake.

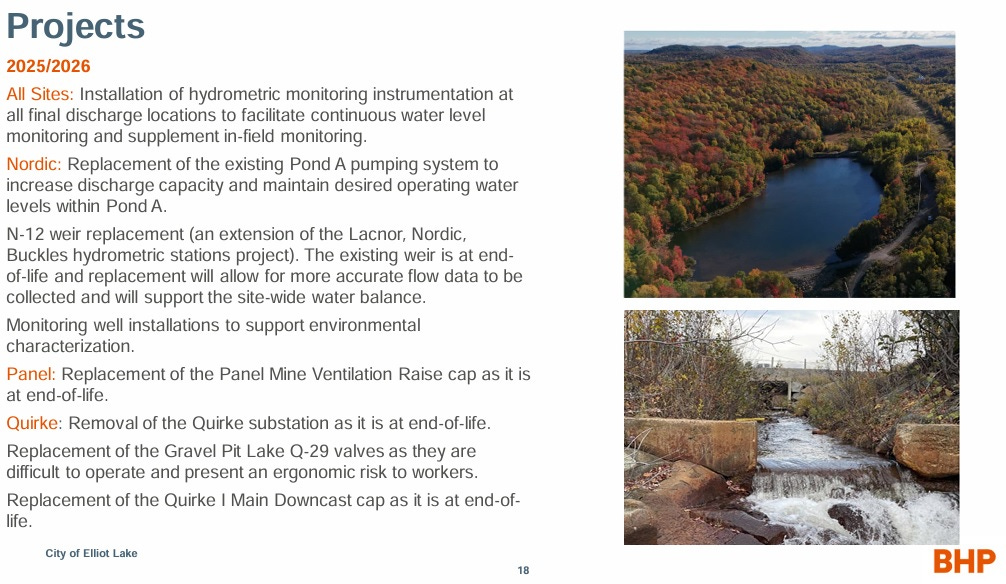

BHP slide showing some of the projected work for this year.

According to the CNSC, protecting ground water and watersheds around tailings sites is essential to the health of local communities. The waste rock and sandy mine tailings are stored under water to control dust, limit oxidization, and provide radiation shielding. The shield water is then processed and treated to remove contaminants.

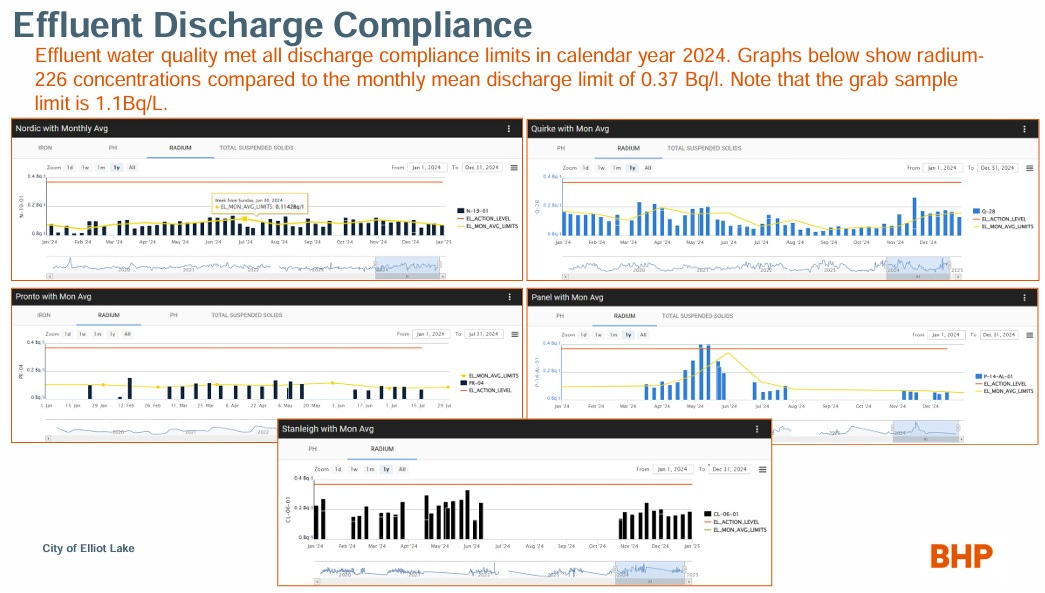

BHP slide showing compliance in effluent discharge testing.

Denison Mines continues to monitor and maintain its two sites in Elliot Lake, and reports to the CNSC each year. This year’s report (on last year’s testing) shows some radium-226 exceedances in sampling, but concludes “results were within values typically observed at this location.”

Neither Denison nor BHP’s responsibility appears to extend, immediately at least, to the problem of radon in certain Elliot Lake homes built atop mining waste rock. A 2023 University of Toronto article about radioactive infill in Elliot Lake mentions that BHP is looking at the issue. Shore Report contacted the company for comment but has yet to receive a response.

As well, during the Elliot Lake extraction years, a notorious sulphuric acid plant was built on Serpent River First Nation (SRFN). Sulphuric acid was used in the processing of local uranium ore. While the plant only operated for roughly a decade — it was decommissioned and destroyed after the uranium boom passed — it left a legacy of severe environmental damage at the First Nation.

SRWMP Annual Report for 2024. Image courtesy Denison Mines.

Rio Algom and Denison Mines continue with the Serpent River Watershed Monitoring Program (SRWMP), which also returns an annual report to CNSC. This year’s report on last year’s testing concludes “that water quality concentrations are stable, continue to meet assessment criteria, and that the area is continuing to recover since the decommissioning of the mines in the area.”

The book Serpent River Resurgence details a history of environmental damage. Image courtesy University of Toronto Press.

Serpent River First Nation itself continues with clean-up and remediation efforts to this day, funded by Indigenous Services Canada. Last year three local environmental activists won the Eugene Rogers Environmental Award for their ongoing work protecting the Serpent River watershed. The book Serpent River Resurgence by scholar and SRFN member Lianne C. Leddy details the colonial forces leading to SRFN’s environmental degradation, and the work of the First Nation to recover.

Since last fall’s revelation that Ontario is planning to ship niobium waste rock from Nipissing First Nation near North Bay to the Agnew Lake Tailings Management Area northwest of Nairn Center, local councils have been busy registering their protest to the apparent lack of consultation. A Special Town Hall Meeting last September included revelations of a degraded tailings cap at Agnew Lake, and the need for immediate repair. The local shock and concern around Agnew Lake stand in stark contrast to what appears to be forthright and responsible stewardship of waste sites elsewhere in the region.

Watch for Part Two of The Radioactive Waste in Our Backyard — What’s on the Way